선이정2025-10-03 14:21:35

[30th BIFF daily] A voice remaining through time

Interview with Sepideh Farsi, director of

May 2025, just before the opening of the Cannes film festival. More than 380 figures in film industry published a letter declaring "We cannot remain silent about the genocide unfolding in Gaza". Among the signatories were Hollywood actors like Susan Sarandon, Ralph Fiennes, and Mark Ruffalo, renowned directors including Pedro Almodóvar, and Jonathan Glazer, who had mentioned Gaza with trembling hands right after winning an Oscar for 〈The Zone of Interest〉. These names came together to honor one name: Fatima Hassona, a Palestinian photographer and journalist.

Fatima Hassona’s story is captured in the documentary 〈Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk〉, which had its world premiere in the ACID section at Cannes, and its Asian premiere at this year’s Busan International Film Festival. I met the film’s director, Sepideh Farsi, in Busan. She is Iranian, a woman who lived through revolution and imprisonment, and had to leave for France at the age of 18. She is also a close friend of Fatima Hassona.

I struggled with how much of this story to include—where to begin and where to end. But unusually, I decided to share everything I heard in this interview, just as it was told. It’s going to be a long read, but some stories must be simmered slowly, like medicine, and taken in gently, no matter how long they are. If your heart has been wounded by the horrors unfolding in Gaza, if you’ve ever felt helpless wondering what you could possibly do—then I hope you’ll read this.

세피데 파르시 감독

세피데 파르시 감독

It’s such a pleasure to meet you here at the Busan International Film Festival. You had your first Q&A session with the audience yesterday—how did it feel?

It was great. The audience’s feedback was really strong and it was also a new experience for me to show the film to the Korean audience. Also, it was the Asian premiere so it does feel very special. The film has been going around the world a lot but this was the first time in Asia and in Korea.

I think the audience would feel closely connected, as Korea has also experienced deep historical pain.

That’s exactly what I felt. When I mentioned that in Q&A session— there are experiences of hardship, famine, and siege during World War II (under Japanese colonization). I'm sure people could relate to it very strong.

Still, the ending of this film was unpredictable. Of course, documentaries are unpredictable about its ending when starting it, but this film ended with a particularly difficult for everyone and especially for you. It wasn’t part of your original plan—so when you first began, how were you planning about the ending of this film?

Well, the film you see now apart from the very last minutes which I added afterwards was the one already it was ready. When Fatem—I call her Fatem like close friends— sent a video that she did to me, I know that I had the ending of the film.

I worked with Fatem for a year. We had video calls and became close very quickly as you see in the film. It was basically interviewing her while filming her, but it was rather our conversations than the interview. I knew that the main line of the film would be our conversations. Very quickly I started editing and the film emerged quite quickly.

It was early spring that I'd sent it for the Cannes. The film was there already when selection happened. I learned it, I told her, and following day she was killed—assassinated by the Israeli army—I'll tell you later how exactly we know that it was a target at that time. It was a target attack usually done similarly for other journalists in Lebanon and Palestine.

I was firstly very shocked and of course and I didn't expect it at all to be, but I thought that I would not change the film, that I would not change anything in the file. I left it as it was. Then I decided just before the Cannes screening—the world premiere— to add this little bit of our last conversation to the film.

The word "assassination" is not used lightly—it’s backed by a detailed investigation that it was not a random strike. But even before that, it’s important to acknowledge that the bombardment was so relentless and indiscriminate that dying from a “random” strike wouldn’t have been surprising either.

In 《Gaza Catastrophe: the Genoside in World》, Gilbert Achcar cites a New York Times article from November 25, 2023, describing the scale of the attacks: 15,000 airstrikes between October 7 and the declaration of a ceasefire. It’s not just the quantity—it’s the deliberate cruelty behind those numbers. If that number feels too abstract to grasp, consider this: look at what Fatem’s world had become.

Israel is using 2,000-pound bombs rarely seen since World War II, far larger than those typically used in modern urban warfare. As a result, Civilian casualties in Gaza within seven weeks are already two-thirds of those in the nine-month battle for Mosul. Strikingly, about 70% of the victims are women and children, a rate unmatched in recent wars.

The reason I say that it is an assassination, a targeted attack it that there was a study conducted by an NGO called 'Forensic Architecture', based in Goldsmiths University in London. They investigate the extrajudicial assassination in different countries and they've done a lot of work about Palestine and Gaza. They had access to some photos and videos of her house filmed from inside after the attack, and through the ballistic studies and 3D modeling, they concluded that it was a targeted attack.

They sent a drone and the drone dropped two missiles on the top of the building where she was living. The missiles were designed not to explode as they hit, but to go through three floors and to explode only on the second floor where she was living. They knew it would kill everybody. They knew it perfectly because the blast was so strong that the concrete column is curved and the floor was wiped, but the building itself is okay. Everybody died except her mother. It was not just a random bombing. They really planned it and they did it. It's so diabolic and I feel strange to describe such an act.

I don't know if it was just linked to her photography or the selection of the film. Even though her name was not announced for the protection. I was afraid and I thought we have to get her out, as we've discussed in the film.

Fatem was living in 2nd floor. (source: FA report, https://share.google/LAJxPYmphqVIqnDk2)

Fatem was living in 2nd floor. (source: FA report, https://share.google/LAJxPYmphqVIqnDk2)

I’ve read several articles about the targeted killings of journalists, but I had vaguely imagined it as simply locating someone’s home and bombing it. That alone is terrible... but to calculate someone’s death with such precision—to design and execute technology that reflects such intent—is so terrifying that I found myself stunned, unable to think for a moment.

Does the people who carried out this operation know that they, with their own hands, have enacted "the banality of evil"? Why does history keep repeating itself in such monstrous forms? People who once read the diary of a young woman who feared death “just for being Jewish” are now looking into the eyes of a woman who died “just for being born Palestinian in Gaza.” And this horrific repetition is not the first time.

In the film, you mentioned that seeing her was like looking into a mirror. As an audience, I felt that too. You, unable to return to the place where you were born, and Fatem, unable to leave hers—it felt like a mirrored reflection. What was it like when you first met this mirror-like Fatem?

I can't explain it exactly but we really felt it in the first conversation. The conversation that opens the film is the very first one that we had together. It was not logical but I think it was more in terms of feelings that emotionally we knew immediately between us.

I know the feeling of being blocked. I was blocked in my own country. I was jailed when I was 16 for almost a year. Then I was blocked. I could not go back to school. I could not go to the university. I had to just sit at home and read books or so, and once a week I had to go to the revolutionary guards and sign up to say what I had done for a week until I was later able to leave the country at the age of 18 and a half. So, for more than 2 years, I was totally like a prisoner—first in prison and then at home.

It goes back to a long time ago and I can't compare it with what happens to Palestinians in Gaza, but I do have a notion of this; how it feels to be blocked. Also, I started with photography when I was 16. These helped a lot to relate to her and perhaps she felt that; that's why she opened to me.

The emotional connection between you and Fatem was clearly visible to the audience. Another mirrored aspect I felt was this: you, as the director, travel widely around the world through your films, yet those places are not shown much in the film—instead, we mostly see screens. On the other hand, Fatem lives in one of the most closed-off places in the world, Gaza, but through her photographs, she opens the streets and alleys to us. It felt like a reversed reality, like a mirror image. Through this film, it felt as though you were expanding and opening up Fatem’s world. Fatem often spoke about wanting to travel, mentioning places like amusement parks and Rome. If you could take her somewhere—beyond the places she mentioned—where would you want to go with her?

I really wanted her to come and see my places. Of course, Tehran is also one of the places but I myself cannot go back for now… but I wanted to go to Gaza. First of all, that was our common plan.

And yes, I would have loved to bring her to the festivals I was going to. The initial plan was Cannes but generally, I wanted her to see. I was also concerned that she might be shocked by the contrast, but this was part of life and... I was prepared to accompany her to face the outside world but never happened.

It felt even more heartbreaking because it was so close. I see this film not only as a precious record of your relationship with Fatem, but also as the conversation and documentation of two artists about the madness of this era. And it's not the first madness that the humanity sees and experiences. Thinking about your life and experiences, I’d like to ask—on behalf of the next generation—do you still believe that society and history are moving toward something better?

Well, that's a hard question. When I arrived in France 41 years ago, it was kind of “free Europe” that was going away from all the authoritarian fascism of 30s and 40s. It was an opening world to many things. I certainly got welcomed in that Europe, in France namely but generally in Europe, and I could find a place in the society while remaining who I am—an Iranian woman.

But nowadays the space of freedom is shrinking. Europe is closing and the world also generally—I don't have much experience about Asian countries, and there's also cases like what happened in Korea last year; the resistance that Koreans did against the strange movement and the martial law. It was great that people realized how important it was to resist immediately and stood up quickly. This awareness is that we're lacking in many societies, such as in USA and Europe generally. I think the world is going towards a more protectionist and conservative stance, political stance and human stance both.

It's bad that we've never had so much access to technology, knowledge, and to so much richness and resources, yet they are not divided properly. The social gap is ever bigger. Some are even richer and many are getting poorer. Also, we have the genocides and the wars. Technologies is being used against the people, instead of being used for people.

I've lived most of my life in Europe, and the "European values" are something that I used to believe in but I think now it's very hollow and they're doing something different with what they were saying. This is very disappointing, and I think really it's time for people to wake up. Of course there are some people resisting, not quite a few, but in terms of governments and the leadership, we are very far from where we should be.

We should be responsive, for instance, against the genocide towards Palestinians in Gaza. This is totally inacceptable. But we see the opportunism and blindness from the politicians. It's the bad side of the politics—maybe politics has become a profession, a business or a career. Earlier for many decades or centuries, it was more like a matter of conviction and faith. I'm not saying that all were great people but there always were people who would show what they believe and what they fight for. Nowadays many working for their own careers and this is very disappointing.

While many politicians remain silent, we’re also seeing more voices from those in the culture industry. Recently, French actress Adèle Haenel joined a flotilla for Gaza, saying, “I could no longer bear doing nothing.” Some people, like her, take immediate action. But many others—though deeply disturbed by what’s happening in Gaza—not knowing what they can actually do. Some say even mentioning Gaza feels politically charged and makes it hard to act.

This is the problem. You see: we've been brought to believe that Palestine is an exception— it is NOT an exception. If—wherever in the world— you kill children, if you kill civilian and innocent people, if you kill journalists, it's a war crime. It doesn't matter who is. The law should be same for everybody. When Israelis do, it's because "they needed to do it", "they had to", for the "self defense". This is not true. That's not correct and this is the problem.

I think there has been a propaganda that has been imposed after the World War II and I understand that what happened there was a total horror and it had to be stopped and punished. But it's not that one genocide had happened so that we have to allow another one to make up for the first one. And it's even worse because we know it now and we see it live. It's streamed. People say that they don't know what to do, but I think there's always something you can find to do.

What would be, for example?

Well, finding NGOs working in Gaza, talking about Palestine, writing about Palestine, sharing news about Palestine, demanding that something need to be done about Palestine, rallies, protests, asking for the government to take stands... You know, it's not easy but I think it's doable for sure.

Think of when Vietnam War was happening. It was not easy to stop it but people were fighting for a long time until the American government change the stance. Same for Apartheid in South Africa. It took decades but people from inside and outside were fighting together. It's also far but I remember clearly that people were fighting in Europe, too.

Civil right movement in America for the "Black Lives Matter", and "Women, Life, Freedom" in Iran... which had a lot of support—and requires a lot more. I don't see any difference with the case of Palestinians. I think we have to do the same thing.

I think imagining something beyond what we’ve always done can be difficult at first—but there are so many references in history we can draw from. With this heart, what keeps you going as an artist? Fatem once said she had a voice in her head telling her to “capture” with her camera. What is your motivation or inspiration for you?

Well, it's more like an obsession in my case. When I work on a project, at some point it takes over my mind and I have to take care of it or I get busy with it. So I get in this case.

The main reason was that I was very, very disturbed by the dominant narrative in the media. They talked about Palestinians as thought they were not human beings. They disregarded their rights, talking instead of them. They were not even interviewing Palestinian victims' families on how they were feeling about this. They were just assuming and other people were talking about them, instead of them. It became very disturbing to me. As an Iranian, I also know that, because it does happen to Iran, to Iranians. I mean Western media; they presume that they know what we feel and what we think. They talk instead of us. And this really got on top of my head and I needed to find out a personal answer for myself.

So, the idea of film started from a personal need, and then I needed to share it with the audience and that's usually how it works. It comes from my heart or my guts and then I share the results with the world.

You’ve shared a story the world truly needed to hear. That question and that heart have reached mine as well. Lastly, could you describe how Fatem was? I hope your description on her would stay with the audience.

First of all… every time I watch the file, I feel she's still alive—beyond life. It's hard for me say that she "was", because I feel she still "is" here somewhere watching us. She was a believer of God—I don't, but I respect her faith—, so I hope she's somewhere watching all that's happening.

And she is a solar, very solar person. When I think of her, I think of lights and illumination. She had such a force and energy in her—a lot of hope, energy and resilience. And the very particular eye: the way she photographed her country and her people is very particular, a mixture of something very rigorous and as intransigent but also very tender. She had these two things mixed in her works and her photography. She was also a great poet. She used to write and she shared quite a few texts with me. I really liked a lot.

I think she had so much to give to the world. She was curious and wanted to travel. She was open-minded. For instance, she believed in God and I said I was not, but I never felt she had kind of a negative reaction. She was very open and respectful and I felt the same way towards her. This was the beauty of our relationship.

She was a great and extraordinary person, and at the same time, a young woman—also a very ordinary one. She had desires like many other young women in her age. By the way, yesterday after the screening, there was a young Korean lady who asked me a question about what to do in Gaza told me that she was Fatem's age that she felt very impacted by what happened to her. Most of us are so lucky to be living the life that we are living, while the Palestinian youth are deprived from all their rights.

She was born in Gaza in 2000 and she was killed in Gaza in 2025. She never left that piece of land. All that she did, all that she learned—she gave to the world from that little room of Gaza as she used to call it in the big house of the world. This metaphor is from her text. I think we lost a great person.

I saw deep affection and sorrow in Director Farsi’s eyes as she spoke about who Fatem was. It reminded me of the days, years ago, after watching the film 〈The Dream Song〉, a movie inspired by the Sewol Ferry tragedy, when I couldn’t sleep for a week.

I’d lie down trying to get asleep, only to suddenly sit up in tears, thinking, “But my love is out there, in that sea—how can I go on living?” It was a time when I truly realized that some people have lived with that feeling for years. And that feeling returned as I looked into the eyes of Fatem and Director Farsi through〈Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk〉.

I think of Fatem—someone I might have met that day, greeted with a bright smile, shared a conversation with. Someone I might have become friends with. Someone who already feels like a friend.

I imagine her walking through the alleys of Gaza, holding her camera as if holding a soul in her hands. I hear her voice—resonant, unwavering—wanting to send a message to the world. And I believe that writing and reading this article is, in itself, an echo in response to that voice.

Relative contents

-

- 눈에는 눈, 믿음에는 믿음

한 마디로 역겹다.

영화를 보는 내내 역겨움이 울컥울컥 차올랐다. 오해는 않았으면 좋겠다. 영화 내의 장면이 구역질 난다던가, 영화가 전하고자 하는 내용이 싫다는 것이 아니다. 영화는 지극히 현실적이고, 그래서 역겨웠다. 이게 현실에 기반한 이야기라는 것이, 이 넓은 세상 어딘가에서는 영화와 같은 일들이 벌어질 것이라는 사실이. 참을 수 없이 역겨웠다. 영화가 끝날 때까지 이런 감정을 유지하게 만들었다는 사실에서, 영화는 극찬을 받아 마땅하다.

감독은 인터뷰에서 영화의 의도를 명확히 밝힌다. 어떤 믿음을 강요하는 자의 입장이 되어보려고 했다고. 그런 사람에겐 믿고 있는 세상이 전부일 것이라고. 그래서 영화에서 던지는 메시지가 그리 어렵게 느껴지진 않았다. 오히려 너무 정확해서 보이는 그대로 받아들여졌다.

영화 속에 등장하는 아이들은 모두 상처를 가지고 있다. 몸매에 대한 강박 때문에 거식증을 앓는 엄마를 따라 어려서부터 음식에 거부감을 느꼈던 엘사, 학부모회의 수장인 부모님의 간섭에 지친 라그나, 이혼하고 홀로 자신을 키우는 엄마를 위해 장학금을 받아야 한다는 압박을 느끼는 벤, 모든 가족이 해외에 나가 자신에게 무관심한 프레드까지. 대체로 가족과 얽혀있는 상처들은 어린 나이에 쉽사리 해결할 수 있는 것이 아니다.

미스 노백은 바로 그 점을 이용한다. 불안정한 심리를 파고들어 아이들의 마음을 쓰다듬는 것이다. 의지할 곳 없던 아이들은 어느 순간부터 선생님이라는 믿음직한 어른에게 자신의 모든 것을 내어놓게 된다. 미스 노백은 아이들의 미묘한 심리 변화를 포착한 후, 섬세하고 치밀하게 상처를 헤집는다. 그렇게 아이들의 지배자가 되는 것이다.

미스 노백은 아이들의 육체에 대한 주도권을 선점하고, 차차 정신을 지배해나간다. 바로 이 모든 과정이 날 역겹게 만들었다.

사춘기 아이들은 반항은 하지만 저항력은 현저히 떨어진다. 일명 '반골 기질'이라 불리듯, 모든 강요받는 것들에 대해 극렬한 거부를 하긴 하지만, 이것을 '왜' 하지 말아야 하는지에 대해 설명하기란 어려운 것이다. 자신을 옭아매는 시스템에 대해 스스로 의문을 품고, 끊임없이 생각하는 능력을 길러, 자신만의 태도로 행동하는 데에는 시간이 걸린다.

그런 아이 곁에 모든 걸 포용해 주는 어른은 거의 없다. 자기 방식대로 밀어붙이거나, 부드러운 말투를 쓰지만 결국 자신의 말만 하거나, 아예 관심이 없거나. 때론 아이에게 부담을 갖지 않아도 된다고 말해주는 어른도 있지만, 너무 일찍 철든 아이들에게는 소용이 없다는 것이 슬픈 현실이다.

이 시점에 아이들에게 필요한 것은 지대한 관심과 들어주는 태도이다. 무언가를 말하고 조언하려는 것은 어른의 방식이다. 하지만 자신의 생각을 말하고 표현하고 싶어 하는 아이들 앞에서는 그저 들어주는 것만이 전부이다. 그게 아이의 마음을 이해하기 위한 시작점이니까.

노백 선생 같은 자에게는 청중으로부터 고립된 아이들이야말로 딱 좋은 먹잇감이다. 먼저 이야기를 들으며 약점을 찾아내면 소극적이지만 분명하게, 자신의 신념인 식사법을 권유한다. 가장 먼저 그 식사법으로 효과를 본 프레드를 바탕으로 더 많은 아이들에게 설파한다. 아이들은 또래 집단의 분위기에 따라 행동이 좌우되기도 한다. 실제로 영화 속에서 '헬렌'은 그저 아이들과 친해지기 위해, 그룹에 끼고 싶어서 수업을 유지한 것으로 보인다.

아이들은 식사법을 공유하는 그룹에 속해 있으면 자신의 외로움과 상처가 치유될 것이라고 믿는다. '친구'라는 존재가 우선되는 것이 아닌, '식사법'이라는 요법이 우선되는 것이다. 그것이 노백 선생에 대한 맹신으로 이어지고, 아이들은 점차 걷잡을 수 없이 말라간다.

왜 하필 식이요법이었을까? 이 질문에 대한 해답은 먹었던 것을 게워내는 엘사의 모습에서 찾을 수 있다.

음식을 먹는다는 것은 몸에 필요한 영양분을 제공하는 것과 같다. 음식을 지식으로 치환한다면 정신을 형성하는데 도움이 되는 영양분을 섭취하는 것이라고 볼 수 있다. 그러나 아이들은 이미 세상에 놓여져 있는 지식을 거부한다. 이것을 삼키면 그들에게 지배당하기 때문이다, 기득권인 어른에게. 아이들의 심리를 잘 알고 있던 노백은 그것을 먹을 필요가 없으며, 먹지 않아도 살 수 있다고 강조한다.

그에 반해 영화에서는 어른이 식사하는 장면을 자주 보여준다. 학교 교장인 도싯은 노백이 앞에 있음에도 불구하고 차에 설탕과 우유를 타고 과자를 먹는 등의 행동을 보인다. 게다가 학부모들은 식사하는 장면을 끊임없이 보여주는데, 심지어는 학부모 회의를 할 때마저도 무언가를 먹고 있다. 그들에게는 누군가의 생각을 쳐낼 힘이 있다. 자신에게 필요하다고 생각하는 지식은 습득하고, 필요하지 않다고 생각하는 것은 버릴 의지가 있다. 그게 과하면 치우친 어른이 되지만, 어쨌거나 그런 힘이 있다는 것만으로도 그들에게는 행동의 자유가 주어진다.

지식이라는 단어는 표면적으로 보이는 것에 비해 깊은 단어다. 사람에게는 지식이 있어야 그것을 응용할 지혜가 생기고, 그런 지혜가 모여 삶의 태도와 가치관을 만들기 때문이다. 그러나 개인적 삶의 근간이 되는 지식 자체를 거부해버리면 아무것도 쌓이지 않는다. 그 무엇도 만들어낼 수가 없다. 노백의 방식은 아이들이 다른 지식에 접근하지 못하게 함으로써 온전히 자신에게만 의존하도록 하는 세뇌에 가깝다. 쉬운 예시를 들어볼까? 당장 보이스피싱만 해도, 다른 사람과 접촉하지 못하게 하지 않는가? 타인이 수상한 낌새를 채면 안 되니까.

결국 아이들은 크리스마스 아침에 노백 선생과 사라져버린다. 자신의 방에 걸어두었던 액자 속 풍경에 들어간 미스 노백과 아이들. 명확한 지명을 밝히지 않은 걸로 보아선, 그들에게 있어 유토피아와 걸맞은 장소일 듯하다. 먹지 않아도 살 수 있는, 영생할 수 있는 곳. 아이러니하게도 죽음이 아닐까. 노백 선생의 이름은 'no back'이란 발음과 똑같다. 다신 돌아오지 않는다. 그들은 모두가 행복할 수 있는 곳으로 가기 위해 함께 죽음을 택하지 않았을까.

더불어 그 장면에서 묘하게 노백의 모습 역시 아이들과 같다고 느꼈다. 마땅히 기댈 변변찮은 어른이 없어, 고통 속에서 자랐을 것이라고. 아이들에게서 자신을 발견한 노백은 그들을 구원해야겠다고 생각했을 것이다. 그것만큼은 진심이었겠지.

이 영화에서 중요한 것은 미스 노백이 설파하고자 했던 신념도, 그것의 근간이 되는 자본주의에 대한 비판도, 진보적이고 올바른 교육에 대한 논의도 아니다. 정말 눈여겨봐야 할 것은 그 결과다. 미스 노백의 신념에 의해 아이들은 어떻게 되었는지, 자본주의는 그것을 해결해 줄 수 있었는지, 치우친 교육이 남긴 흔적은 무엇인지.

아이를 잃은 학부모들은 학교에 모인다. 스키장에 가느라 노백을 만나지 못했던 헬렌은 유일하게 살아남은 학생이다. 헬렌에게 노백을 따른 이유를 묻지만, 이미 세뇌된 헬렌 역시 노백의 말을 그저 앵무새처럼 따라 할 뿐이다. 유일하게 어른들 중에서 식사를 거부했던 엘사의 엄마는 '우리도 먹지 않으면 아이들을 이해할 수 있을까?'라고 묻는다. 하지만 헬렌은 '믿음의 문제'라고 말하며 영화가 끝난다.

지식을 습득하는 데에는 믿음이 필요하지 않다. 오히려 믿음을 가지면 위험할 때도 있다. 지식의 섭취는 오로지 지식에 의거했을 경우에만 유용하다. 빈 속에는 식이섬유와 채소부터 먹고 단백질, 탄수화물 순서로 먹는 것이 좋다는 식으로 말이다. 합리적으로 지식을 습득하는 것은 경험에 의한 것이지 믿음에 의한 것이 아니다.

그러나 지식을 습득하지 않으려면 믿음이 필요하다. 무언가를 거부할 때는 그에 반하는 믿음이 필요한 것이다. 이것을 거부해야만 마땅한 이유 말이다. 현대 사회에는 아직 그것을 가려낼 힘이 없는 아이들을 꼬드겨 그릇된 믿음을 심어주는 자들로 가득하다. 그런 자들로부터 아이들을 어떻게 지켜내야 할까?

아이러니하게도 믿음이다.

아이를 믿고, 그 아이의 마음과 생각에 관심을 갖고, 귀를 열어야 한다.

아이에 대한 믿음만이, 아이를 잘못된 길로 인도하는 믿음으로부터 구할 유일한 방법인 것이다.

-

- 8월 4주 최신 개봉영화

2022년 8월 4주 개봉영화!

불릿트레인 Bullet Train , 2022

브래드 피트가 다시 돌아왔다!

영화 "불릿 트레인"는 미션을 수행하기 위해 초고속 열차에 탑승한 언럭키 가이 '레이디 버그'가 전 세계 고스펙 킬러들과 맞닥뜨리면서 펼쳐지는 논스톱 액션 블록버스터입니다.

3년 만의 주연으로 브래드 피트는 이너피스를 꿈꾸는 언럭키 가이 ‘레이디버그’로 분해 열연을 펼칩니다.

여기에 할리우드의 새로운 액션 장르 강자로 꼽히는 데이빗 레이치 감독만의 장기를 더해 독창적이고 스타일리시한 액션을 완성시켰습니다.

'데드풀 2', '분노의 질주: 홉스&쇼', '존 윅'으로 액션 장르의 새로운 히어로로 자리 잡은 데이빗 레이치 감독과 브래드 피트의 만남으로

전 세계 영화 팬들의 폭발적인 관심을 불러일으키고 있습니다.

초고속 열차에서 벌어지는 고스펙 킬러들의 피 튀기는 전쟁!

추천영화 "불릿트레인" 입니다.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

사랑할 땐 누구나 최악이 된다

VERDENS VERSTE MENNESKE , THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD , 2021

작품성과 흥행 모두 잡은 역대급 신드롬

칸영화제에서 여우주연상을 수상하고 아카데미 시상식에서 각본상, 국제장편영화상 후보에 오르며 작품성을 입증한 "사랑할 땐 누구나 최악이 된다"는

내 삶의 조연은 그만하고 싶은 스물아홉 '율리에'가 인생의 다음 챕터로 달려나가기까지, 그 아프지만 반짝이는 여정을 그린 영화로,

'라우더 댄 밤즈', '델마' 등으로 국내 영화팬들에게도 익숙한 요아킴 트리에 감독의 신작입니다.

"고전적인 할리우드 로맨틱 코미디를 현대적으로 재해석한 작품이며,

한계에 직면하면서도 스스로 자아를 찾아가는 여성을 통해 그곳에서 나오는 모든 코미디와 혼돈을 포착하고 싶었다”라고 이야기해 더욱 기대를 높이고 있습니다.

버락 오바마 전 미국 대통령 또한 자신이 애정하는 2021년 영화 리스트에 등록된

추천영화 "사랑할 땐 누구나 최악이 된다" 입니다.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

육사오 2022

올여름 스트레스를 날려줄 유일무이 코미디!

영화 "육사오"는 바람을 타고 군사분계선을 넘어가버린 57억 1등 로또를 둘러싼 남북 군인들간의 코믹 접선극입니다.

운명처럼 말년 병장의 발 밑에 날아온 로또 한장이 57억 1등 당첨 로또였다는 기상천외한 상상에,

심지어는 그 로또가 바람을 타고 군사분계선을 넘어 북으로 안착한다는 기절초풍할 설정을 더했는데요

고경표, 이이경, 음문석, 박세완, 곽동연, 이순원, 김민호 자타공인 코미디 강자부터 은둔 고수까지!

긍정 에너지 넘치는 배우들의 빵빵 터지는 코믹 케미스트가 기대가 되는 영화 입니다.

'공동경비구역 JSA 이후 남과 북 청춘들의 이야기'라고 말한 박규태 감독은 "육사오"에는 현재 충무로의 '영 블러드'들이 한 데 모여 막강의 케미스트리를 만들어냈습니다.

'날아라 허동구' 연출, '달마야 놀자', '박수건달' 각본 등 유쾌한 상상력에 오랜 기간 쌓아온 노하우를 더해

언제나 기분 좋은 웃음을 선물하는 박규태 감독!

57억 1등 당첨 로또를 둘러싼 남북 군인들간의 코믹 접선극!

추천영화 "육사오" 입니다.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

큐브 CUBE 一度入ったら , CUBE , 2022

25년 만에 허락된 '큐브' 첫 공식 리메이크

영화 "큐브"는 살인 함정이 가득한 정육면체 공간에서 벗어나려는 생존자 6명의 사투를 그린 밀실 탈출 호러로, 올여름 호러 기대작으로 주목받고 있는데요.

1997년 원작 '큐브'가 공개되고 간단한 설정이지만 기발한 아이디어가 넘치는 이 영화에 영화 팬들의 뜨거운 지지가 이어졌었죠

그동안 수많은 '큐브'의 후속편이 공개되어 왔지만 새로운 "큐브"는 빈센조 나탈리 감독이 직접 크리에이티브에 참여한 작품이라 더욱더 기대가 큽니다.

엔지니어, 편의점 아르바이트, 학생, 정비공, 기업 임원!

어떤 접점도 없는 평범한 사람들이 큐브에서 펼쳐지는 살인 게임!

원작을 유지하면서 새로운 큐브를 만들어 낸

추천영화 "큐브" 입니다.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

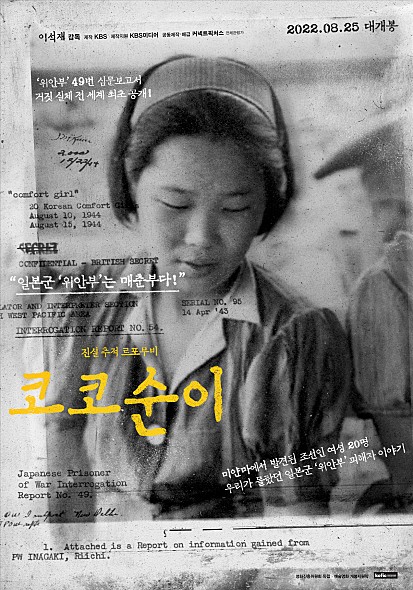

코코순이 KOKO SunYi , 2022

OWI 49번 심문보고서 거짓 실체 전 세계 최초 공개

영화 "코코순이"는 강제 동원된 '위안부' 피해자 중 미얀마에서 발견된 조선인 포로 20명을 심문한 보고서에 남겨진

일본군 '위안부'에 관한 왜곡된 기록과 감춰진 진실을 밝히는 추적 르포무비입니다.

일본군 '위안부' 피해자를 매춘부로 매도하는 일본 우익단체와 관련인들의 근거가 되고 있는 미 전시정보국 49번 심문보고서의 거짓 실체를 전 세계 최초로 밝힌다는 점에서 더욱 특별하죠.

영화 '코코순이'는 다양한 사회 문제와 진실을 심도 깊게 파헤쳐온 KBS 탐사 프로그램 '시사기획 창'의 촬영팀과 제작팀이 참여하고

이석재 기자가 연출을 맡아 완성도 높은 르포무비를 탄생시켰습니다.

2022년미 하원의 '일본군'위안부' 사죄 결의안(HR121)' 통과 15주년과 세계 일본군'위안부' 기림일' 공식 제정 10회차로 의미가 특별한

추천영화 '코코순이'입니다.

-

- 혹성탈출 4 | 아직은 오지 않은 '새로운 시대'

* 스포일러가 있습니다.

진화한 유인원과 퇴화한 인간들이 살아가는 땅. 성년식을 기다리던 '노아'(오웬 티그)와 독수리 부족은 갑작스레 '프록시무스 시저'(케빈 듀랜드) 군대의 습격을 받는다. 노아는 혈투 끝에 간신히 살아남지만, 아버지는 죽고 모든 부족은 프록시무스 시저의 왕국으로 끌려간다. 이에 노아는 부족을 구출하고 아버지의 복수를 이루기 위한 여정에 나선다.

아무도 믿을 수 없는 여행길에서 고생하던 노아는 우연히 두 친구를 만난다. 유인원 '라카'(피터 메이컨)는 노아에게 전설적인 유인원 지도자 '시저'의 가르침을 알려준다. 또 자신처럼 프록시무스 시저에게 쫓기던 인간 소녀 '메이'(프레이아 앨런)는 노아에게 유인원과 인간의 과거, 현재, 미래를 알려준다. 이러한 도움을 토대로 노아는 시저의 가르침을 기만하는 프록시무스를 무찌르고 유인원과 인간 모두를 구할 전투에 나선다.

4편의 저주에 걸리다

의도하지는 않았겠지만, 2024년 봄 극장가는 4편으로 가득하다. <쿵푸팬더 4>가 긴 공백을 깨고 돌아왔고, <범죄도시4>는 천만 관객을 돌파했다. 다만 성과는 기대 이하다. <쿵푸팬더 4>는 지난 시리즈의 매력과 캐릭터에만 기댈 뿐이었다. <범죄도시4> 역시 여전한 흥행 파워를 과시했지만, 장기 시리즈의 피로감은 가중됐다.

<혹성탈출: 새로운 시대>(이하 <혹성탈출4>)는 올봄의 세 번째 '4편'이다. 2011년에 리부트 된 시리즈의 4편이고, <혹성탈출: 종의 전쟁> 이후 7년 만의 속편이다. 그런데 제목이 퍽 흥미롭다. 지난 삼부작으로부터 직접적으로 이어지는 속편인데도 불구하고, 제목에서 '4'라는 넘버링을 활용하지 않았다. 이로부터는 시리즈의 새 출발을 보여주려는 의도가 엿보인다. 지난 주인공인 '시저'(앤디 서키스)를 등장시키지 않듯이.

하지만 <혹성탈출4>도 '4의 저주'를 벗어나지 못했다. 지난 시리즈의 메시지와 주제의식을 적절히 계승한 전개를 보여주지만, 비주얼을 제외한 대부분이 오리지널리티가 부족하다. 그 결과 4편까지 이어진 시리즈에 신선한 피를 수혈할 작품이냐고 묻는다면 고개를 선뜻 끄덕이기는 어렵다.

시리즈의 정수를 계승하다

<혹성탈출>의 핵심은 유인원과 인류의 대립이다. 하지만 거대한 스케일의 전쟁만 화두가 되지는 않았다. 시저에게는 인간 친구가 여럿 있었다. 자기를 키워준 윌. 아내를 치료해 준 말콤. 인간을 향한 복수심과 증오심을 꺾어 준 소녀 노바. 의견이 다른 유인원 및 인간과의 충돌에도 불구하고 시저가 인류와의 공존을 추구한 이유였다. 이처럼 사적 감정을 공적 책무로 승화하는 시저의 여정은 <혹성탈출>의 드라마를 특별하게 만들었다.

전편으로부터 300여 년 후를 다루는 <혹성탈출4>도 마찬가지다. 이번에도 종족 간의 전쟁 사이에서 싹을 틔우는 두 유인원과 인간의 관계를 다룬다. 인류를 무시하는 유인원 노아와 유인원에게 사냥당하던 인간 메이는 우연히 같이 여행을 떠난다. 노아는 프록시무스 시저에게 붙잡혀 간 자기 부족을 구출하기 위해. 메이는 인류의 미래를 건 임무를 수행하던 중에.

물론 둘은 서로를 완전히 신뢰하지 않는다. 자기 종족의 존속이라는 목표가 언제나 최우선이기 때문. 하지만 서로에 대한 오해와 편견을 조금씩 덜어내면서 둘은 우정 비슷한 관계까지 나아간다. 친구는 아니지만, 차마 서로를 죽이지는 못하는 관계로. 서로가 서로를 죽여야 미래의 화근을 잘라낼 수 있는데도. 그렇게 <혹성탈출4>는 재개될 유인원과 인류의 전쟁을 미묘한 애증의 감정선 속에 포함시키는 데 성공한다.

아이디어는 좋았다

앞선 시리즈의 계승만큼 프랜차이즈를 일신하려는 노력도 엿보인다. 유인원 대 인간의 대립 구도뿐만 아니라 유인원 간의 갈등에도 초점을 맞춘다. 노아와 프록시무스 시저는 인간과 공존할지, 아니면 인간을 제거하고 지구를 차지할지를 두고 다툰다. 이는 2편 <반격의 서막> 속 시저와 코바의 대립을 극대화한 듯 보인다.

이름만 봐도 두 주인공의 대립은 필연적이다. 성경에서 노아는 신의 뜻에 충실한 유일한 인간이었다. 그래서 그는 방주를 만들어 대홍수로부터 모든 생명체를 구할 수 있었다. 영화 속 노아도 마찬가지다. 그는 "유인원은 뭉치면 강하다"와 "유인원은 유인원을 죽이지 않는다"라는 시저의 말을 제대로 이해한 유일한 유인원이다. 그래서 그는 나름의 방주를 만들어 시저의 뜻대로 인간과의 공존을 모색하는 리더로 거듭난다.

반면에 프록시무스 시저는 시저를 사칭한다. 인간과 유인원을 모두 지배하는 왕국을 만들고, 인간의 기술력을 손에 넣기 위해서 "유인원은 뭉치면 강하다"라는 가르침을 악용한다. 그 과정에서 죽어가는 유인원은 신경 쓰지 않는다. 라틴어로 '가장 가까운'이라는 의미를 지닌 '프록시마(Proxima)'를 이름으로 쓰지만, 정작 시저가 가장 지양할 선택만 지향한다.

이에 더해 노아와 프록시무스 시저의 대립은 종교적으로 해석할 여지가 있기에 더욱 흥미롭다. 여러 세대가 지난 뒤 시저는 숭배의 대상이 됐고, 노아와 프록시무스 시저는 시저의 후계자 자리를 두고 다툰다. 마치 예수의 가르침을 두고 여러 교파가 싸웠듯이. 또 무함마드의 후계자 자격을 두고 수니와 시아가 전쟁을 벌였듯이. 이렇게 보면 <혹성탈출4>는 <혹성탈출> 버전 <듄>이 될 수도 있었다.

스토리텔링의 한계

그러나 기존 삼부작과 차별화될 가능성은 미처 꽃 피우지 못했다. 제작진의 스토리텔링 역량이 뒷받침되지 않기 때문. 영화는 두 주인공의 본질적인 차이를 보여줄 다양한 맥락과 복합적인 함의를 외면한다. 일례로 프록시무스 시저의 왕국을 묘사할 때는 정복 전쟁, 노예제, '시저'라는 호칭처럼 고대 로마를 연상케 하는 요소를 활용한 반면, 노아와 프록시무스 시저의 대립은 단순히 부족의 생존과 탈출 차원으로 국한시킨다.

그러다 보니 여러 장치도 제대로 활용되지 못한다. 독수리 부족의 통과 의례가 대표적이다. 노아의 부족에게는 독수리 알을 훔쳐 키우는 성년식이 있다. 이때 둥지마다 최소한 알 하나는 남겨둬야 한다는 규칙이 있다. 이는 독수리 부족이 본질적으로 타 생명체와의 공존을 추구한다는 점을 암시한다. 하지만 영화는 노아와 독수리의 관계를 개인적 차원에만 국한한다. 노아에게 독수리는 부족의 리더로 거듭나고 아버지의 복수를 완수하는 도구일 뿐이다. 결국 미묘한 함의는 끝내 전해지지 않는다.

스토리텔링 문제는 메이의 묘사에서도 드러난다. 노아 혹은 유인원의 관점에서 이야기를 풀어가다 보니 메이는 철저히 인간중심적이고, 노아의 행보를 방해하는 빌런처럼 보인다. 인류와 유인원의 대립은 극대화되지만, 둘 사이에 작게나마 피어난 우정의 싹은 더욱 작아진다. 그 결과 서사는 다소 평면적이고, 지난 삼부작에 비해 인간 캐릭터의 매력도 찾아보기 어렵다.

뒷심 부족한 볼거리

볼거리 역시 아쉬움이 적지 않다. 물론 <메이즈 러너> 시리즈의 웨스 볼 감독이 새로 메가폰을 잡은 만큼 전체적인 스타일의 변화는 인상적이다. 이전 감독인 맷 리브스가 전반적으로 정적인 분위기를 유지하다가 순간적으로 에너지를 분출하는 연출력을 과시한 반면, 이번에는 유인원과 인간의 추격전처럼 역동적인 카메라워크가 눈길을 끈다.

이에 더해 포스트 아포칼립스 영화 제작 경험을 살려 수풀로 뒤덮인 도시와 철골구조, 녹슨 배와 무너진 부두로 만든 프록시무스 시저의 왕국 등의 디스토피아 세계관도 유려하게 펼쳐 보인다. 그뿐만이 아니다. <라이온 킹> 실사 영화가 사자를 비롯한 동물의 표정을 효과적으로 구현하지 못했던 것과는 달리, 유인원들의 미세한 표정 변화도 놓치지 않고 포착한 CG 기술력은 감탄을 자아낸다.

하지만 후반부로 갈수록 스펙터클은 약해진다. 이전 시리즈에 비해 스케일이 소소하다 보니 <캐리비안의 해적: 낯선 조류>를 보는 것 같은 실망감이 밀려들 수 있다. 특히 클라이맥스의 구성이 아쉽다. 노아와 프록시무스 시저의 대결은 공격도 반격도 일방적이라서 긴장감을 조성하는 데 한계가 있다. 노아와 결속된 독수리를 활용하는 아이디어도 암시가 너무 많아서 반전이라고 보기는 어렵다.

결국 공은 속편에게

결과적으로 <혹성탈출4>의 결말은 아쉬움이 크다. 독립된 작품이면 모르겠지만, 네 번째 시리즈에서도 인간과 유인원의 전쟁을 다시 한번 암시하는 결말은 신선함이 부족하다. 돌고 돌아 시저의 이야기를 반복하는 게 아닌가 싶기 때문. 여러 프랜차이즈가 같은 실수를 범했기에 특히 우려스럽다. 시리즈 리부트 후에도 매그니토와 프로페서 X의 갈등 구도를 마지막까지 되풀이 한 <엑스맨> 시리즈가 대표적이다.

결국 공은 속편에게 넘어간 듯하다. 속편의 전개에 따라 <혹성탈출4>가 새로운 시대를 위한 한 걸음일지가 결정될 테니. 달리 말해 어떤 의미로든 속편을 기다리는 재미만큼은 분명해 보인다.

Acceptable 무난함

진짜 무대는 다음으로 미루는 예고편

-

- 엄청난 액션에 가려진 킬러의 감성

지친 뒷모습을 한 사람이 계단을 계속 올라가려 시도한다. 그의 주변에는 그가 더 이상 올라가지 못하게 막는 사람들로 가득하다. 몇 번을 쓰러지고 두들겨 맞아도 다시 일어서는 그 남자는 수많은 방해에도 불구하고 다시 계단을 오르기 시작한다. 그의 어깨는 축 쳐졌고 무척 외로워 보인다. 존 윅(키아누 리브스)이라는 이름을 가진 그는 죽은 자신의 아내가 남긴 강아지와 함께 살다가 그 강아지 마저 죽자 그 복수를 시작으로 계속된 공격을 받아봤다.

<존 윅4>에서 존 윅은 모든 사람에게 공격받는 위치에 있다. 하지만 그는 그 모든 상황을 정리하기 위해 하나의 목표를 향해 나아간다. 이렇게 어쩔 수 없이 하나의 목표로 계속 걸어가야 할 때가 있다. 주변 사람들이 자신을 공격하는 상황이 이어지고 겨우 버티고 있던 몸과 마음도 지쳐간다. 딱 존 윅의 상황이 그런 상황이다. 물러서는 것은 죽음이고 그 싸움에 이긴다고 해서 특별히 상이 주어지는 것도 아니다. 어쩌면 존 윅의 삶은 이미 지옥 안에 있었을 것이다.

액션을 중심으로 이야기를 전개해 나가는 영화

<존 윅> 시리즈는 액션을 중심으로 이야기를 전개시켜 나간다. 1편을 시작으로 4편까지 이어지는 이야기에서 몸을 움직이는 액션은 점점 복잡하고 화려해졌다. 그 자체가 존 윅이라는 캐릭터가 가지고 있는 마음의 상처가 커지는 과정처럼 보인다. 그가 시리즈 초반에 보여주는 권총 액션은 무척 깔끔하고 간결하다. 하지만 자동차 추격을 벌이거나 근접 격투 액션이 이어지면 스케일이 커지면서 인물들의 대결에 집중하게 된다.

시리즈 속에서 온갖 고난을 겪는 존 윅을 바라보는 시선은 기본적으로 애잔함이다. 이 이야기 안에서 가장 유명하고 전설적인 킬러지만 은퇴를 선택한 그를 죽음의 시장에 다시 끌어낸 건 작은 강아지였다. 그러니까 감정이 전혀 없을 것 같은 인물이 무척이나 감성적인 이유로 다시 사람을 죽이기 시작한 것이다. 그리고 수많은 다른 킬러들이 그에게 달려들어 죽이려고 하는 장면이 이어지고 존 윅은 아무 거리낌 없이 죽여나간다. 그럼에도 불구하고 관객은 존 윅을 계속 응원하게 된다. 액션의 통쾌함도 있겠지만 그가 보여주는 감성적인 부분이 더욱 캐릭터에 대한 애착을 높여준다.

어쩌면 영화에 등장하는 강아지들이 그런 감성적인 느낌을 주는지도 모르겠다. 지금까지 나왔던 4편 모두 강아지가 등장하고 심지어는 킬러들과 함께 적을 공격한다. <존 윅4>에도 한 킬러와 함께 등장하는 강아지는 이번에도 존 윅과 그를 돕는 동료들과 함께 싸운다. 존 윅이라는 캐릭터는 시종일관 무표정한 표정으로 앞으로 나아간다. 그는 감성적인 부분을 거의 표현하지 못하지만 그가 강아지를 대할 때나 강아지를 위험으로부터 구할 때 존 윅이라는 캐릭터가 가지고 있는 감성이 그대로 드러난다. 그런 장면들이 반복되면서 영화에 따뜻함을 덧붙여준다.

액션뿐만 아니라 감성적인 공감도 불러오는 이야기

대부분의 사람들이 <존 윅4>의 액션이 훌륭하다고 이야기한다. 맞다. 이 영화에서 보여주는 액션은 무척 다채롭고 빠르고 난이도가 높다. 후반부로 갈수록 대단한 볼거리들이 이어진다. 특히나 후반부 개선문 앞에서 펼쳐지는 카체이싱과 격투액션은 어떤 식으로 촬영했는지 궁금해질 정도로 훌륭하다. 이외에도 중반에 한 저택에서 벌어지는 총격 액션을 위에서 보여주는 장면도 마치 게임 화면을 보는 것처럼 독특한 느낌을 준다.

이런 다양한 액션 장면도 무척 훌륭하지만 이 시리즈 전반에 자리 잡고 있는 존 윅 특유의 감성도 꽤 훌륭하다. 존 윅이라는 캐릭터는 독특한 인물이다. 그는 딱딱해 보이지만 애잔하고, 어떤 면에서는 굉장히 인간적으로 느껴진다. 그가 과거에 차가운 킬러였다는 사실이 믿겨지지 않을 정도로 그는 무척이나 감성적인 인물처럼 보인다. 영화가 존 윅의 뒷모습을 꽤 많은 장면에서 보여주는데 어려운 상대를 연속으로 만난다는 이유도 있겠지만 다른 무엇보다 그의 고단한 삶을 보여주기 위함일 것이다.

영화에서 존 윅에겐 몇 명의 조력자가 등장한다. 이번 4편에서는 킬러들이 쉬는 호텔을 운영했던 윈스턴(이안 맥쉐인)이 유일하다. 물론 후반부가 되면 조력자가 몇 명 더 등장하지만 처음부터 끝까지 존 윅이 앞으로 나아갈 수 있게 돕는 건 윈스턴뿐이다. 윈스터는 본인의 빼앗긴 자리를 다시 되찾으려는 욕망이 무척 큰 인물인데, 한 편으로는 그가 존 윅을 돕는 것이 개인의 욕망 때문으로 보이기도 하지만 다른 한 편으로는 그가 개인적으로 존 윅에게 어떤 동료애를 느끼는 것처럼 보이기도 한다. 말 그대로 윈스턴도 존 윅이라는 캐릭터에 정을 주고 있다는 의미다.

영화의 하이라이트는 계단에서 벌어지는 격투다. 200개가 넘는 그 계단을 모두 올라가야 최후의 결투를 벌일 수 있는 거리에 도착할 수 있다. 존 윅은 이 계단에서 수도 없이 넘어지고 계단을 굴러 떨어진다. 그럼에도 불구하고 그는 무거운 몸을 일으켜 다시 계단 위를 향한다. 어쩌면 그는 궁극적인 삶의 목표를 잃었기 때문에 더욱 조직에 대항하는 그 목표에 집착하게 되었는지도 모른다. 킬러의 세상에서 벗어날 수 있는 자유를 얻기 위해 그는 수많은 적의 공격을 막아내며 계단을 오르는 것을 포기하지 않는다.

영화의 하이라이트 개선문과 계단 액션

우리는 시리즈 안에서 존 윅을 돕는 다양한 인물들을 만났다. 윈스턴을 시작으로 바워리 킹(로렌스 피쉬번), 샤론(랜스 레딕), 소피아(할리 베리), 케인(견자단) 같은 다양한 인물들은 완전한 존 윅의 편이라고 할 수는 없지만 결국 그를 돕게 된다. 그런 일련의 과정은 존 윅이 실제로 다른 킬러들에게 어떤 인물로 다가가는지를 잘 보여준다. 또한 영화에서는 그들은 존 윅의 편에 설지 아니면 반대편에 설지를 적절히 활용하면서 영화의 긴장감을 높인다.

존 윅 역을 맡은 키아누 리브스는 조금은 감정 없고 딱딱해 보이는 킬러로서의 존 윅에 딱 맞는 배우다. 60살이 가까워지고 있는 그의 나이에도 불구하고 액션을 여전히 훌륭하게 소화하고 있다. 무엇보다 그가 연기하는 존 윅의 뒷모습은 무척이나 감성적이면서도 측은함을 느끼게 한다. 이 영화에서 존 윅과 대결을 벌이는 케인 역을 맡은 견자단도 인상적인 액션을 보여준다. 장님역할을 맡은 그는 다양한 도구를 이용해 적을 물리치고 최종적으로 존 윅과 대결을 벌이면서 좋은 장면들을 만들어낸다.

<존 윅> 시리즈가 만들어낸 킬러들의 세계관은 다채로운 액션을 만들어내고 보여주기에 적합한 세계관이다. 앞으로도 이 세계관의 이야기가 더 관객들을 찾을 것으로 보인다. 아나 디아르마스가 주연을 맡은 영화 <발레리나>가 현재 제작 중에 있고, 킬러들이 쉬는 호텔인 콘티넨탈의 이야기를 그린 드라마 <콘티넨탈> 도 제작이 진행되고 있다. 앞으로도 <존 윅>에서 소개된 다양한 킬러들의 다양한 액션과 서사를 다양한 형태로 볼 수 있을 것 같다.

*영화의 스틸컷은 [다음 영화]에서 가져왔으며, 저작권은 영화사에 있습니다.

주간 영화이야기 뉴스레터!

구독하여 읽어보세요 :)

네이버 프리미엄 콘텐츠에서 제 뉴스레터를 구독하실 수 있어요.

https://contents.premium.naver.com/rabbitgumi/rabbitgumi2

-

- 레모네이드의 씁쓸한 맛은 왜 그녀의 몫이 되었나.

여러 시선이 모여 한 방향을 가리키고 있다면 우리는 어느 곳을 봐야 할까. 당연하게도 여러 시선이 모인 한 방향을 봐야 한다고 대답할 것이다. 하지만 실제론 그렇지 않다. 생각보다 사람들은 남에게 관심이 없기 때문이다. 사소한 진실로 인해 발버둥 치듯 현실을 살아가는 한 사람의 이야기를 담은 레모네이드를 소개하려고 한다. 영화의 끝맛이 쓸지 달지는 보는 관점에 달렸다. 루마니아에서 온 마라는 미국인과 결혼하여 아메리칸드림을 꿈꾸고 있다. 다니엘과 함께하며 안정을 찾고 싶은 마라는 사랑해 마지않는 아들도 만났고 이제 영주권만 받으면 된다고 생각한다. 왠지 모를 두려움에 둘러싸인 마라는 여러 문제가 얽혀 있어서 더욱 불안해진다. 다시 돌아갈 수 없는 고향으로 인해 그 상황을 견디려 하지만 포기할 수 없었다. 그렇게 미국인이 되기 위한 발걸음을 내딛지만 그를 대가로 하는 현실을 맞닥뜨린다. 나아갈 수도 없고 뒷걸음칠 수도 없는 마라는 어떤 선택을 하게 될까.

디즈니랜드는 아니지만, 지금보다 더 나은 삶을 위해서 나아가는 수많은 사람은 마라를 통해 비친다. 미국에 정착하기 위해서는 누군가를 책임지고 동시에 잔혹해지며 거짓이 섞인 진실을 타협해야만 했다. 그것이 현실을 살아가기 위한 현실이자 현재였으니까. 이질감과 이분화된 개념들이 소외감을 불러일으켜 버겁게 느껴지지만 그런데도 나아가는 마라의 뒷모습이 인상적이다. 앞으로 나아가는 모습이 우직해서 이 사랑 섞인 환상이 환상이지 않기를 바랐던 마음이 부끄러워지기도 했다. 특정인에게 일어나는 일이 아닌 만큼 영화가 내어주는 분위기가 굉장히 힘들게 느껴졌다. 상황을 전달하는 것도 물론 중요하다고 생각하지만, 그 상황을 어떻게 표현하는지가 굉장히 중요하다. 이 영화는 끊임없이 자기 세계로 빨아들이려는 사람들로 인해 고통스러웠지만 동시에 세상을 살아가는 방식을 깨닫는 방식이 아프게 느껴졌다. 타인의 약점 앞에 선 인간은 한없이 잔혹해지는 것 같다. 아무것도 보이지 않는 안개 속을 헤쳐 나가는 마라가 무사히 살아가길 바라며 이 영화의 달콤씁쓸한 맛을 전한다.

-

- 영화의 모든 단점을 최민식의 연기력으로 덮다

영화 <더 베트맨>을 보러 영화관에 갔을 때 대문짝하게 포스터가 붙어있었던 영화 <이상한 나라의 수학자>. 어떤 내용인지 굉장히 궁금했고, 최민식 배우의 작품이어서 기대를 하며 본 작품이었다.

영화 <이상한 나라의 수학자> 시놉시스

“정답보다 중요한 건 답을 찾는 과정이야”

학문의 자유를 갈망하며 탈북한 천재 수학자 이학성. 그는 자신의 신분과 사연을 숨긴 채 상위 1%의 영재들이 모인 자사고의 경비원으로 살아간다. 차갑고 무뚝뚝한 표정으로 학생들의 기피 대상 1호인 이학성은 어느 날 자신의 정체를 알게 된 뒤 수학을 가르쳐 달라 조르는 수학을 포기한 고등학생 한지우를 만난다. 정답만을 찾는 세상에서 방황하던 한지우에게 올바른 풀이 과정을 찾아나가는 법을 가르치며 이학성 역시 뜻하지 않은 삶의 전환점을 맞게 된다.

* 해당 내용은 네이버영화를 참고했습니다.

이 이후로는 영화 <이상한 나라의 수학자>에 대한 스포일러가 존재합니다.

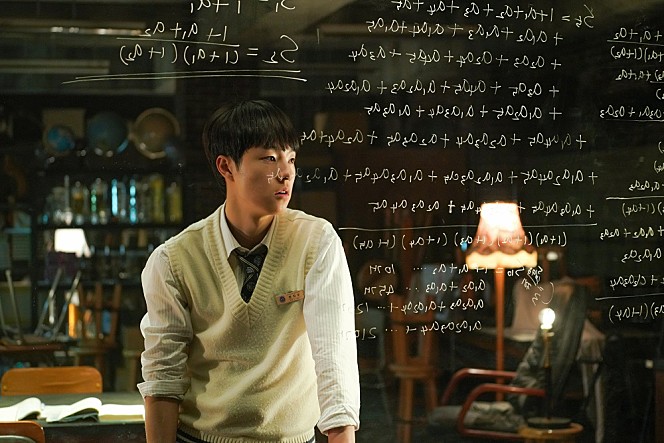

한국 영화의 진정한 클리셰를 모아봤어요영화 <이상한 나라의 수학자>를 한 줄로 평하자면 한국 영화의 클리셰를 한 데 모아 놓은 작품이라고 보면 된다. 수학이라는 소재를 활용했다는 점에서 약간의 독창적인 부분이 있는 것은 사실이었지만 내용의 전재라든지, 클라이맥스로 향하는 그 과정이라든지, 현실에서는 있 수 없는 굉장한 해피엔딩으로 끝나고 있었다.

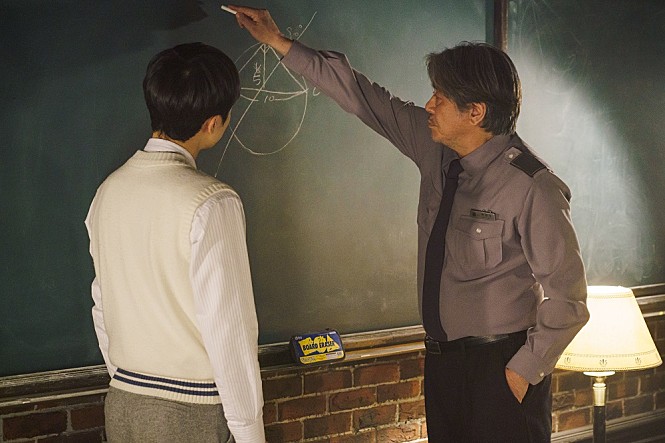

이런 점에서 영화 이상한 나라의 수학자는 한국에서 나고 자란 관객이라면 다음 장면은 이러한 내용이겠지? 이런 대사 한 번은 쳐줘야 되지 않겠어?하는 3초 스포가 자동적으로 되는 작품이다. 하지만 그런 클리셰 속에서도 수학이라는 아름다움을 보여주기 위해 다양한 청각적 요소들을 활용한다거나 칠판의 맞은 편에서 열정적으로 풀이하는 그들의 모습을 보여주는 등 조금은 색다른 카메라 구도를 보여줘서 지루하지 않게 볼 수 있었다.

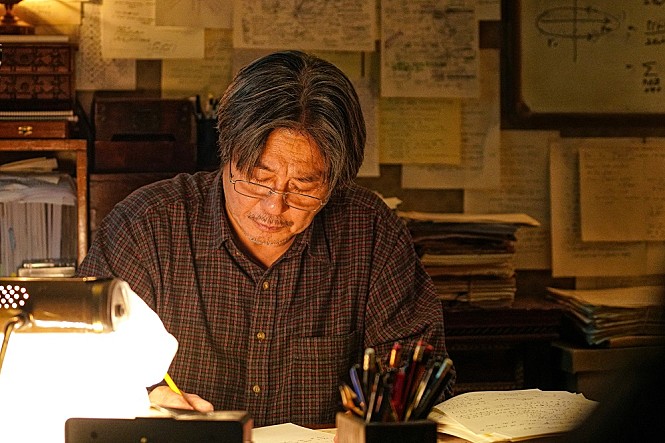

최민식의 연기력은 대단했다

이러한 클리셰 덩어리들이 영화 곳곳에 포진해 있었지만 그럼에도 불구하고 감동을 받은 이유는 무엇일까? 바로 최민식의 연기력 때문이다. 수학을 정말로 사랑하는 그의 모습을 보면서 저렇게까지 사랑할 수 있다고? 공식을 하나 설명하고 해설하는데 저렇게 행복한 표정을 짓는다고? 아름답다고 안 해주니까 세상 무너지는 듯한 실망스러운 표정을 짓는다고? 말을 하지 않아도 표정을 통해서 이 캐릭터가 어떠한 감정인지 너무나도 잘 드러나서 경이로웠다. 만약 표정백과사전이 있다면 거기에 등재되어야 하지 않을까 싶을 정도였다.

찰나의 순간에도 변하는 최민식의 연기를 보면서 저렇게까지 인간의 감정은 다채롭다는 것을 느낄 수 있었고, 행복, 슬픔, 감격, 씁쓸함이 동 떨어져 있는 것이 아니라 복합적으로 표현되는 것이라는 점을 정말 잘 확인할 수 있는 작품이었다. 그 표정을 보면서 그리고 증폭되는 감정연기를 보면서도 단 한순간도 과장됐다는 느낌이 전혀 들지 않았던 것을 보면 왜 최민식 배우를 대한민국의 대표배우라고 하는지 잘 알 수 있었던 작품이었다.

정답을 찾는 것이 중요한 것이 아니다

누구나 아는 말이다. 방향이 중요하지 정답이 중요하지 않다. 모두에게 옳은 정답은 없다. 하지만 치열한 입시 세계 취업 세계에서 이 말은 잘 통하지 않습니다. 내 정답이 아닌 남이 옳다고 생각하는 정답을 내밀어야 사회에서는 '나'를 봐주기 때문이다. 그런 사회를 향해 영화 <이상한 나라의 수학자>는 다시 한 번 방향과 방법이 중요하다, 문제의 답은 그리 중요한 것이 아니다라고 외친다.

사실 그저 그런 영화에서 이러한 메시지를 전달했다면 사회의 현실을 알지 못한다, 누가 그걸 몰라서 그렇게 답만 찾아내는 입시 공부를 하는 줄 아느냐, 어쩔 수 없이 하는 것인데 구조적인 체제를 비판하지 않고 그저 이상적인 소리만 해대면 어떡하냐고 신랄하게 비판을 했을지도 모른다. 하지만 최민식 배우가 주는 강력한 울림은 그런 생각마저 하지 못하게 만들었다. 이래서 왜 작품에서 캐릭터를 연기하는 배우가 얼마나 중요한지를 여실히 깨달을 수 있었다. 굉장히 이상적인 이야기지만 배우의 연기력 만으로도 그 이상적인 이야기에 공감을 하고 반성을 하게 만드는 그 강력한 울림은 이번 작품을 통해서 경험할 수 있었다.

영화 <이상한 나라의 수학자>는 보는 내내 최민식 배우를 찬양할 수밖에 없었던 작품이었다. 영화에서 배우의 중요성을 다시금 깨닫게 해준 영화였다.

-

-

- 원작의 기대에 못미친 오컬트 블록버스터 / 퇴마록 애니메이션 / 원조 퇴마소설

영화직관하는남자 홍큐의 "퇴마록" 후기입니다.

*쿠키영상이 엔드크레딧 전에 하나 있어요~

-

- 영화 <와일드 구스 레이크> 메인 예고편

오토바이 갱단 리더 저우 저농은 실수로 경찰관을 살해한 뒤 현상금이 붙어 경찰과 폭력배 모두에게 쫓기는 신세가 된다. 그는 자신을 돕기 위해 왔다는 여성을 만난 뒤 휴양지 '와일드 구스 레이크'에 몸을 숨기고, 쫓기는 두 사람은 목숨을 건 위험한 도박을 하게 되는데.

-

- 영화 <레전드 스크라이커> 메인 예고편

20세기 소련의 축구 영웅 ‘에두아르드 스트렐초프’, 그의 파란만장했던 일대기!

시골 변두리에 살던 축구 천재 스트렐초프는 소련을 멜버른 올림픽 우승으로 이끌며 온 국민이 사랑하는 최고의 기대주가 된다.

그러나 자유분방한 그를 비판하는 사회주의 세력에 의해 그의 경력은 위기에 처하고, 벼랑 끝의 순간 그는 챔피언의 가치를 스스로 증명해야 한다.